The Third Annual Devolution Conference in Meru, Kenya, April 2016

Devolution is here to last! This message was delivered loud and clear at the Third Annual Devolution Conference in Kenya, organised by the Council of Governors. In three years this conference has become an important gathering of national and county government representatives, academia, private sector and civil society to discuss the benefits and challenges of devolution.

A brief I wrote on water policy choices of Kenya’s 47 county governments sparked interest among national and county governments and led to an invitation to share key findings at the conference to an audience of over 6,000 people.

A new political era for Kenya

Devolution, also known as decentralisation, was set in motion back in 2010 with a new constitution that introduced two tiers of government, the national and county level, and devolved certain functions to the counties, including water and health services. The 2013 elections led to the establishment of 47 county governments with affiliated county water ministries – new institutions that have developed their water service delivery mandate throughout the three-year transition period.

This year’s conference marked the end of the transition period in March 2016, when all functions outlined in the 2010 Constitution become fully devolved. It is also a critical time politically as Kenya’s 2017 national and gubernatorial elections are approaching fast and competition over the Governors’ seats is rising.

The delegates passed 18 resolutions to reinforce devolution and hand over all devolved functions to county governments. Some of the contested functions were the water, health and irrigation sectors.

Managing water services under devolution

Water is one of the mandates divided between national and county governments; it remains a national resource, but water service delivery is now a county responsibility. As water crosses county boundaries, it is clear that national-level institutions are needed to navigate conflicts and regulate water service provision. However, counties are asking for more autonomy and there is a need to avoid duplication of efforts between the national and county institutions.

The research I presented at the conference shows that the water service mandate is interpreted differently by Kenya’s 47 counties. Not all counties acknowledge their responsibility for the human right to water which entitles everyone to sufficient, safe, acceptable, physically accessible and affordable water. This suggests a need for county water policies to be streamlined so that regional disparities don’t grow and transformative development is sustained.

These findings come from a unique opportunity I had to survey all 47 county water ministries in Kenya at a summit organised by the Water Services Trust Fund to develop a prototype Country Water Bill. I found that while counties are making major investments in new infrastructure for water services (where the majority spend more than 75% of their water budgets), maintenance provision and institutional coordination are often neglected. This raises a concern about the sustainability of water services and could slow down progress towards achieving the Sustainable Development Goal for water.

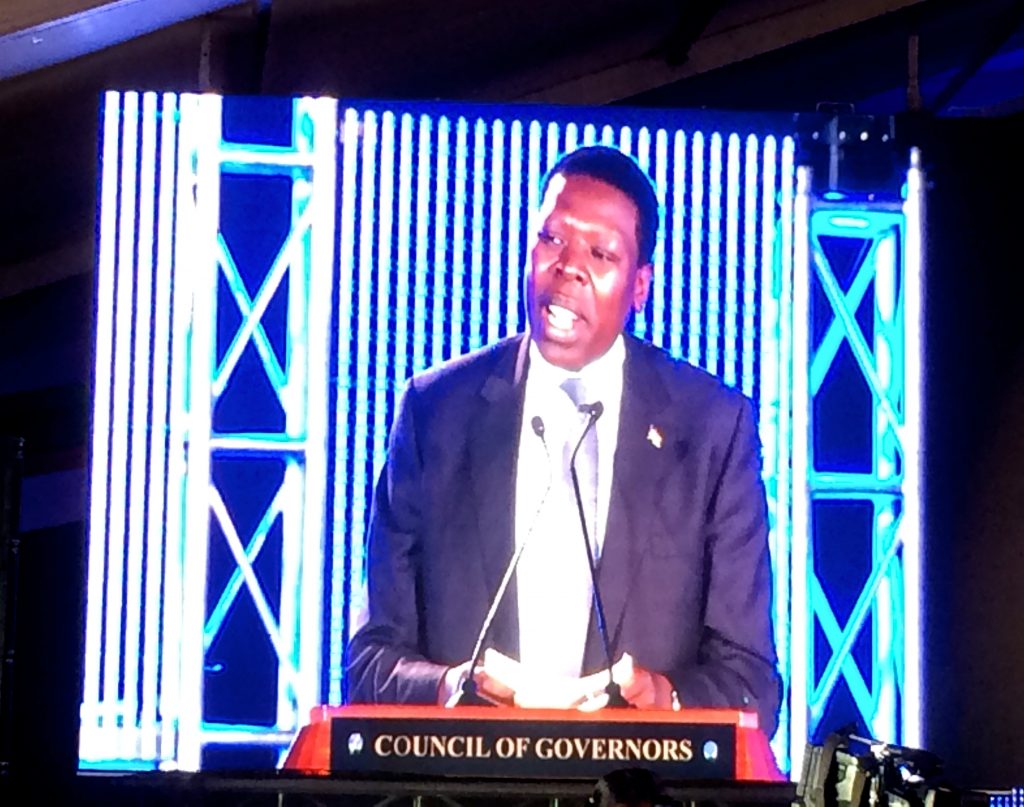

Cabinet Secretary for Water and Irrigation, Eugene Wamalwa, closes the Devolution Conference on behalf of Deputy President of Kenya, H.E. Ruto

Optimistic but uncertain outcomes for the poor

So will devolution lead to more accountable politics and better water services for the poor? This is one of the research questions that the REACH programme is asking in Kenya. A Water Security Observatory in Kitui County aims to understand how institutions can be designed to reduce rural water security risks, for example from rainfall variability, unreliable infrastructure and irregular financial flows.

In the water sector and elsewhere, the Devolution Conference was marked by a strong momentum for change. County governments committed to tackling social inequalities through targeted allocations of funds to relevant sectors, and urged everyone to join the fight against corruption, which is seen as a key obstacle to devolution.

The conference was certainly used as a political tool for building support for devolution. Delegates were told how school attendance has increased because of bursaries provided by Turkana County Government; in Machakos County, people walk shorter distances to get medical attention; Kisii town has a 24-hour economy after the installation of solar lighting; while Mombasa County has introduced a feeding programme for primary school pupils. And so the success stories go on.

Overall, the conference provided an important platform to share progress made in Kenya’s devolution process with the key political actors, and also to flag new or existing challenges as county governments manifest their power. It is remarkable to see such a transformation in Kenya’s political system within the short timeframe of only three years. It seems the water sector will gain from these changes, but only the future will tell if the newly devolved system will benefit the poor.

Read the Policy Brief – Water Policy Choices in Kenya’s 47 Counties