Salome A. Bukachi, Dalmas O. Omia, Mercy M. Musyoka, Faith M. Wambua, Mariah P. Ngutu (University of Nairobi), Marina Korzenevica (University of Oxford)

This blog is derived from an ethnographic study “Gender analysis of vulnerability and resilience to household water insecurity in Kitui County, Kenya: implications for institutional and policy response in the face of climate variability.” The study, funded through one of REACH’s Exploring Inequalities grants, assessed the socio-cultural dynamics and political institutions (both formal and informal) dimensions of household water insecurity. The overarching aim of the study was to conduct a gender analysis of communities’ vulnerability and resilience to household water insecurity in Kitui County, Kenya.

The rural water picture: progress and gaps

Universal access to safe drinking water is anchored in SDG target 6.1 , which aims for equitable access to safe and affordable water for all by 2030. Notable progress has been made towards the attainment of this goal as 2.6 billion people globally have gained access to improved drinking water sources since 1990, increasing from 76% to 91% coverage. However, 663 million people, especially those living in resource-poor rural Sub-Saharan Africa, still have limited access2.

The United Nations estimates that sub-Saharan Africa alone loses over 40 billion hours collecting water annually. Improved drinking water sources are on average 30 minutes or more away for 29% of the continent’s population – 37% in rural areas and 14% in urban areas. Women and girls are often the ones responsible for the collection of water and they end up paying with their time and lose opportunities to engage in other activities.

Achieving SDG 6.1 without leaving anyone behind is challenged by economic aspects such as the cost of purchasing water, severe droughts in addition to human activities including, deforestation and pollution of water bodies. These can impact on rainfall and lead to drying up of groundwater, thus diminishing available ‘free and safe’ water sources. Interventions need to be conscious of and respond to these multiple factors in a comprehensive manner.

Can social capital quench the thirst?

Access to water within rural communities involves more than just the individual woman, girl or household to enable community resilience in the face of water insecurity and climate change. Within the rural set up, women, girls and households engage as neighbours, friends, kin and kith to be able to access water for drinking and domestic uses.

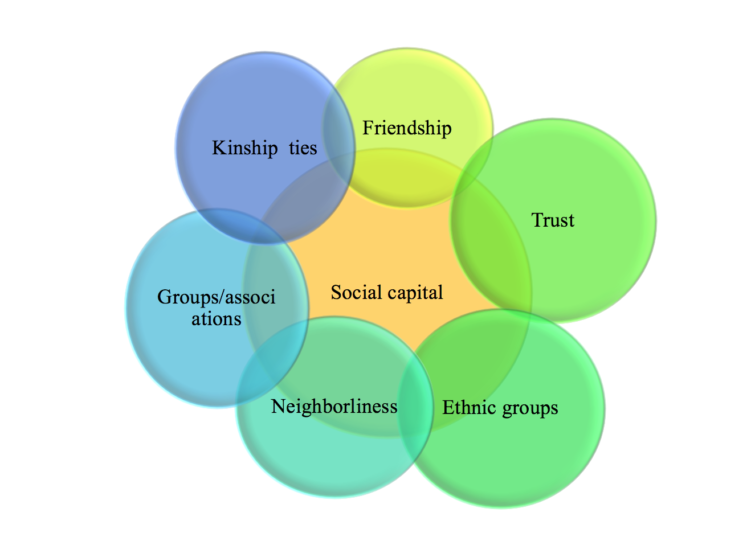

Figure 1: Social capital and water access

This pulling together and taking advantage of existing relationships brings to life the concept of social capital exhibited as: social networks (neighbourliness, groups/associations and friendships) and the social structures (kinship and ethnic groupings). Trust cuts across all these social relations as the cementing glue on both networks and structures.

Communities and individuals therein leverage on these resources, the attributes, norms and beliefs operational within networks and structures in accessing water as illustrated in the excerpts:

“Yes, we help one another, today they help me with water then tomorrow I help them with water. We help one another freely without charging any money at all.” (Female respondent)

“We share amongst ourselves, if you are my neighbour I can borrow from you a jerrican or two of water, if we agreed I will replace the water whenever I will manage to collect my own. If we relate well then I am [more?] open to borrow water from you than if we didn’t relate at all.” (Female respondent).

Social capital was evidenced in exchange practices such as a safety net that ensure water access in difficult situations for different able-bodied people. For instance, the operationalisation of the pay-as-you-go model allows people of diverse social and economic backgrounds to access safe water for drinking and domestic use. Specifically pay-as-you-go refers to accessing water on credit; exchanging water for food equivalents; seasonal one-off payments; cross-borrowing of water ATM cards within neighbourhoods; and collecting water for new mothers, persons with physical disability, and the very elderly. These forms of access are ensured by the existence of good relationships safeguarded by community values, especially trust.

What on a WASH broad scale does social capital respond to?

Importantly, it isn’t the case that reliance on social capital leads some community members to take advantage of others – that is by gaining access to water at the expense of other members’ time and opportunity. Community values modelling the social capital ensures a flexible system of paying for water access either through cash or in-kind based on mutual trust. This means that a household or individual supported to access water today will in the near future return the kindness directly and also indirectly be an enabler for a household in need, to access water.

Given that access to water is a basic right, social capital plays a crucial role in water-scarce rural communities as it ensures:

- Access of water for all, including community members with special needs;

- Acceptability, where community members participate in water production, especially at group/association levels;

- Affordability where in-kind and credit payments allow people to access water while still meeting other competing priorities.

Moving forward:

Social capital as an essential resource for poor communities should be integrated in discussions around the following points:

- Where are the voices of the marginalised and vulnerable in the design and management of water sources? This is key towards inclusive water access.

- How flexible and sensitive are the market-driven water provisions to community-seasonal and in-kind payment modes? Provision of interventions need to take into consideration the socio-cultural contexts of communities to enable tailoring of appropriate interventions, buy-in and sustainability of programs

- Does group membership exclude non-members from accessing water? This is critical to note because entry to community if done solely through groups may exclude those most vulnerable who may not afford to be in a group due to lack of finances to pay for membership fees.