Nancy Gladstone, Professor Rob Hope, Dr Johanna Koehler, Florence Tanui, Cliff Nyaga, Dr Jacob Katuva

This blog is based on research from REACH and the USAID Sustainable WASH Systems Learning Partnership – read the full report.

Today is International Women’s Day which recognises the role and contribution of women in all aspects of society. The theme for 2021 is ‘to choose to challenge’. Our contribution is to challenge the inequality in delivering safely-managed water to Kenyan schools, which affects girls, their future prospects and wider society.

We know women with higher education are healthier, they engage more in work and can earn more, they marry later and have fewer children, and they provide better health and education to their children. Water in schools may seem a rather indirect approach to supporting education until you go beyond the public data to understand the scale of the challenge, but also the opportunities to respond.

In Kenya, there are 20 million children of school age, around 40% of the population. They attend around 50,000 primary and secondary schools. Reflecting the wider population, seven out of ten people live in rural areas where drinking water service provision is often unreliable and of poor quality. In Kitui county, the 2019 census found two out of five people state surface water from streams, rivers or wells is their main source of drinking water. We found schools face similar challenges in the provision of safe and reliable drinking water. In each school, the head teacher is responsible for the school’s water, making 50,000 water managers doing their best, often on their own.

What does this mean for girls?

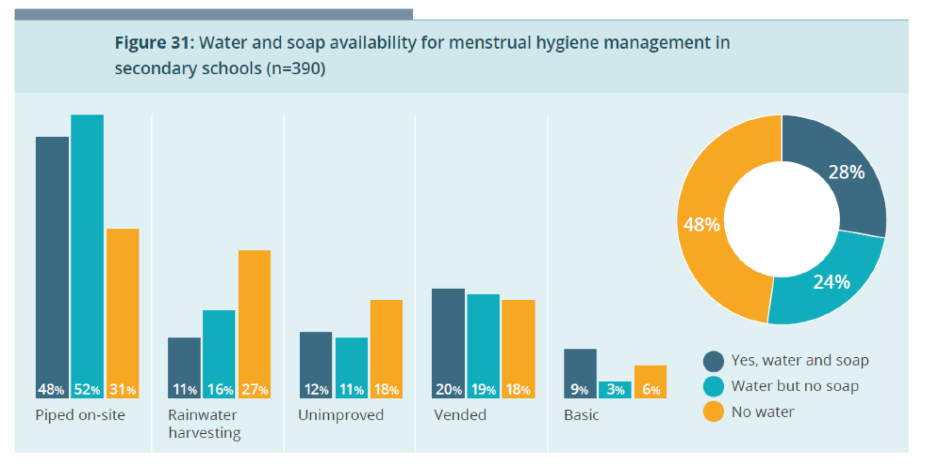

Our data from 1,887 schools in Kitui county found male teachers did not associate water concerns with menstrual hygiene management (MHM). Female teachers did but they represent one third of the total of 3,141 staff. One in two secondary schools reported no water for MHM. While one in five schools had a piped supply on site this did not lead to better outcomes as these schools reported the highest share without water from MHM. Just because a school has a piped supply does not mean it has any water or that the water is safe to drink.

National and county governments have inherited a legacy of poor water supply in rural schools. Funds are available to build classrooms and pay salaries, but the provision for water or other services is limited and competes with books, electricity, sanitation or meals. We found one in three schools spent no money on water in the 12 months before the survey. This challenge is compounded by the COVID-19 crisis as handwashing facilities are essential to contain the spread of the virus.

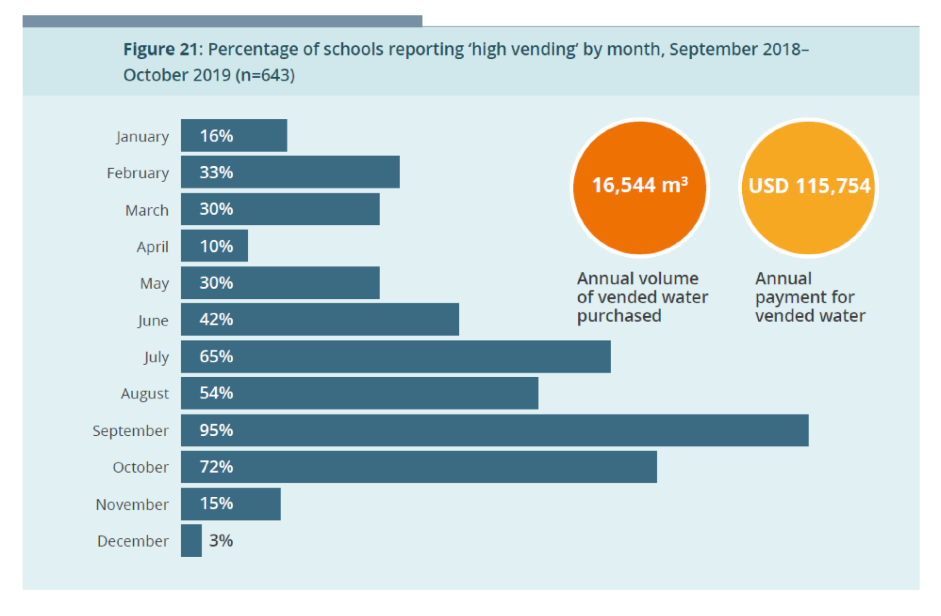

Alternatively, one third of schools spent a total of USD115,754 on purchasing vended water during the dry months. Despite four out of five schools reporting a rainwater harvesting tank, as a good way to capture seasonal rains, the dry season spans many months leaving all schools at risk. Vendors plug the gap at a cost for those schools willing and able to pay. Tankers and push carts delivered 16,544 m3 of water, the majority in the dry months from June through October.

What can be done?

REACH’s collaboration with the SWS Learning Partnership and UNICEF has been supporting the development of a results-based maintenance company called FundiFix. Established in 2016, FundiFix guarantees to fix failures fast for a small fee to communities and schools. Rather than the usual month or more to fix a simple fault, FundiFix fixes waterpoints in a few days. The company has now introduced water quality monitoring which has revealed multiple hazards in most schools.

REACH’s future work will support national and county governments to deliver the constitutional right to safe water for all citizens established in 2010. The COVID-19 crisis exposed the gap in water service delivery in cities and rural areas leaving millions of children without a safe environment to study for nearly a year. FundiFix operated during the crisis keeping water flowing in rural areas demonstrating a model that could contribute to new policy and practice by national and county governments to benefit every girl and boy attending school.